Food is medicine, and what we put into our bodies matters a great deal. With a balanced diet of healthy and organic food, the risk for diseases, such as cancer and diabetes, is decreased while brain function and mood are increased. Beyond the individual, food wellness is often passed down generations in practice.

Food deserts, mostly found in urban and rural areas, are defined as places with no access to affordable healthy food options due to distance from a grocery store and the abundance of fast-food restaurants. So when nearly half of the tens of millions of people living in food deserts are low-income, with Black people and other POC disproportionately represented, it’s obvious that this is an issue of consequence. It’s not a matter of making specific choices on what to eat — there is often no real choice at all. Feasibly, it’s hard to justify a 30-minute drive to a grocery store instead of a 5-minute walk to a McDonald’s (not to mention a $6 bunch of organic spinach instead of a $2 bunch of “conventionally-grown” spinach), even considering all of the harmful chemicals that the extra cost would avoid. The system forces its people to consume for their wallets, not for their health.

“The system forces its people to consume for their wallets, not for their health.”

Like other facets of the American economy, Black people are extremely underrepresented in the leading producers of the farming community. According to the 2012 Census of Agriculture, Black people represent less than two percent of the nation’s farmers. This indubitably comes down to the multitude of added challenges that Black farmers face: racial discrimination from the banks who give farmers loans, the Farm Service Agency, the USDA. The NYTimes’ podcast 1619, especially Episode 5: The Land of Our Fathers, is a great source for a more detailed explanation on this subject.

American agribusiness’s focus on corn and soy subsidies, in which the government pays farmers to plant corn and soy crops, exacerbates the problematic production of cheaper versus nutritious food. Smaller farmers who support their land and community are often driven out of business. The counterintuitive practice of big agro’s monoculture system of agriculture, where a single crop species is repeatedly planted in a large expanse of land with no other plant species present, lacks the food diversity necessary for fertile soil while introducing the need for polluting pesticides. Shockingly, many smaller farms running a completely organic operation do not apply for the USDA certification of organic farming, as it requires incredibly extensive recordkeeping that farmers simply can’t justify while running their business as an individual. Meanwhile, big corporations have plenty of resources to market themselves as certified organic, even if the mid-sized-to-small farms are more sustainable in their processes.

In urban communities trapped in food deserts, many people are rising against this issue. Realizing the impact of the lack of resources, activists such as Ron Finley are demonstrating how food can be fit into the cracks of a city: from the rooftops to the sidewalks, there is opportunity to garden. Recently, more inspiration came from Seattle’s CHAZ (Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone), where Marcus Henderson, founder of Black Star Farmers, started a community garden at Cal Anderson Park. However, community gardens in urban areas are often faced with the threat of lack of clean water. Marcus Henderson’s garden is currently at risk of losing such access and you can sign this petition to help preserve the garden.

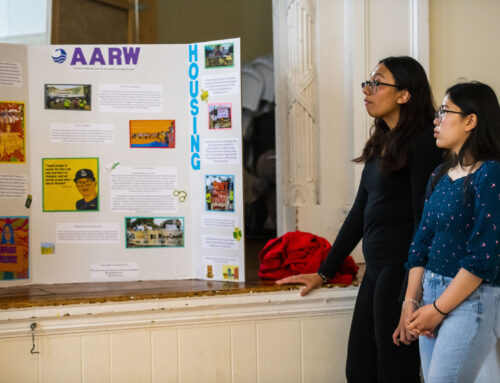

Meanwhile, the solutions in some rural communities affected by a lack of access to healthy foods include Farmshare CSAs (Community-Supported Agriculture), where people sign up for a program to receive fresh vegetables and other crops directly from their local farmers. While this can seem like a luxury, this is an excellent example of a functioning food system. Farmers provide for their community while their community provides for them: the cycle in perfect harmony. In addition, many CSAs accept EBT Food Stamps to ensure that people from all economic levels can utilize the service. For example, farmer and activist Leah Penniman created the Soul Fire Farm Share, which delivers freshly grown produce to members in Troy and Albany. No one is turned away due to lack of income and the program offers #solidarityshares for immigrants, refugees, and those impacted by state violence. Soul Fire Farm’s goal is to end racism and injustice in the food system and provides many educational opportunities, including a Black and Latinx farmers immersion, an uprooting racism immersion, a youth program, and activist retreats.

While there are many amazing activists and community leaders working to improve access to healthy foods at an affordable cost, the reality is that clean eating continues to be a privilege and not a choice. We need to work towards a system that no longer disproportionately allocate essential resources. Everyone needs regular access to healthy, organic food. And it needs to be treated like the necessity that it is.

Featured image: Courtesy of Soul Fire Farm, edited by Chloe Xiang